Administrator’s note:

Forty years ago, the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and its instrument

in the South, the National Liberation Front (NLF), dastardly violated the truce

agreement and launched a general attack in

During the three-week occupation of the Imperial City of Hue in

1968, the NVA and NLF premeditatedly executed approximately 7,000 South

Vietnamese, mostly city employees and their families. A German correspondent

for Springer News Service, Mr. Uwe Siemon-Netto was present in

As a former Vietnamese

combatant of the war in

The Persistence of Memory Four decades after covering the communist Tet Offensive in Vietnam, a veteran correspondent explores the new Saigon in California – and remembers – By Uwe Siemon-Netto

Launched four decades ago, the Tet Offensive was a turning point in the Vietnam War. It ended in a military disaster for Hanoi but Americans perceived it as a defeat for their side. Soon after, the U.S. began withdrawing from the conflict. This writer covered the campaign as a German correspondent. This year, he spent Tet, the lunar new year holiday, amid 200,000 Vietnamese immigrants in Orange County, California.

Launched four decades ago, the Tet Offensive was a turning point in the Vietnam War. It ended in a military disaster for Hanoi but Americans perceived it as a defeat for their side. Soon after, the U.S. began withdrawing from the conflict. This writer covered the campaign as a German correspondent. This year, he spent Tet, the lunar new year holiday, amid 200,000 Vietnamese immigrants in Orange County, California.

In the basement of St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Garden Grove, California, Vietnamese toddlers clad in colorful Ao Dai gowns welcomed the Year of the Rat with a cheerful dance on the stage. Next, Mark Siegert, a theology student, sang Vietnamese folk songs, karaoke-style. Revelers at round tables devoured spring rolls doused with nuoc mam, a fermented fish sauce.

To my right, Hung Dinh Pham, the congregation’s president, was in a more somber mood. “I was a judge in Saigon when you were there,” he said to me. “For this ‘crime,’ the Communists incarcerated me for seven years in a North Vietnamese re-education camp after their victory in 1975. During all that time, I never heard from my family.” After his release, Hung fled in a rickety boat across the South China Sea and almost drowned like tens of thousands of his compatriots. A French naval vessel rescued him.

I heard many such wrenching tales as I explored Orange County’s vibrant “Little Saigon” on the Tet Offensive’s 40th anniversary. None intrigued me more than the story of Ton That Di, an electronics engineer who had lost six members of his immediate family during the bloodiest event of the entire war.

Ton That drove me in his black Mercedes to Little Saigon’s enchanting open-air markets, shops and restaurants displaying the former South Vietnamese flag: three horizontal red stripes on a bright yellow background.

Then he took me to an evening memorial service for the tens of thousands of his compatriots who were slaughtered at Tet ’68. Outside the City Hall of Westminster, California, clergy from three religions stood at an elaborate altar − Buddhist monks, Protestant pastors and a white-robed priest of the Cao Dai faith that venerates Jesus, Mother Buddha, the Prophet Muhammad, William Shakespeare, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Thomas Jefferson, Napoleon, Lenin and Churchill.

Meanwhile, an elderly bard in a brilliant blue robe chanted a haunting acclamation to the dead, punctuated by eerie notes from an exotic wind instrument.

Among the mourners were former generals and colonels including Ton That’s father-in-law on whose head the Vietcong had once placed a $1 million bounty. After his escape to California, he worked as a parking lot attendant while his wife, a teacher, labored in a factory. Yet the couple managed to put their two daughters through university: Both are now dentists.

What fascinated me most about my encounter with Ton That was the discovery that our fates had strangely intersected in 1968. He is a member of Vietnam’s imperial family. But his father was one of those humble civil servants I always pitied as I watched them through their office windows shuffling mounds of paper in the Social Services Department one block up Tu Do Street from my hotel, the Continental Palace in Saigon.

Ton That and I reminisced much about the early days of 1968 just before the Vietnamese Year of the Tiger became so bloody. I had actually gone to Laos, certain that nothing would happen in Saigon during the Tet ceasefire that both sides in this war had promised to keep. However, in the cool Laotian mountains, I met a French major who told me, “If I were a journalist I would rush back to Saigon at once because all hell’s going to break loose there.” Knowing the excellence of French military intelligence in Indochina in those days, I heeded his counsel and flew back.

Just about that time, Ton That’s father was at Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut Airport boarding an Air Vietnam DC 6 for Hue, the former imperial capital. “He wanted to be with my grandpa on his 80th birthday,” said Ton That, who was left behind to look after his mother and baby sister. All Vietnamese celebrate their birthdays on New Year’s Day.

“I never saw dad again − we found no trace of his body. Two of his brothers and three of my cousins also disappeared,” Ton That recalled dolefully as we passed Phuoc Loc Tho, a Vietnamese shopping center on Bolsa Avenue in Westminster, the heart of Little Saigon. This pulsating market houses dozens of jewelry stores, clothing and herbal shops all owned by refugees who have prospered in California.

At the shopping center’s altar, worshipers lit joss sticks before a fierce-looking deity, representing a general of ages past, while next door in front of a dental clinic cheerful fortune seekers won and lost their dollars in a game called High and Low at makeshift gambling tables. But Ton That’s mind was elsewhere: “At least my grandfather survived in 1968. I don’t know how.”

He pulled out a map of Hue and pointed to a neighborhood named Vi Da on the northeastern bank of the River of Perfumes. “This is where grandpa’s house stood,” he said. I was dumbfounded: I was literally next door when the North Vietnamese led my new friend’s father, uncles and cousins to their deaths.

I had joined the Fifth U.S. Marines as they fought their way into Communist-occupied Hue. The road from their staging area at Phu Bai Airport was strewn with the bodies of men, women and children, all festively clad to welcome the New Year, and all shot through the head by the northern invaders.

There were so many that the leathernecks had to move them out of the way to avoid driving over these corpses with their tanks, trucks and armored personnel carriers. This scene flashed back into my mind as Ton That spoke about his family.

We journalists were housed in the local compound of the U.S. Military Assistance Command. We slept on concrete floors under paper body bags. A demented goose had fled into this stark place. Every time we heard exchanges between American M-16 and Soviet-made AK-47 assault rifles nearby, the crazed animal crept under our covers. Often we heard volleys from the area just north of us. Now I know: This was the area where grandfather Ton That lived.

I never went in this direction, though. I went south along Le Loi Boulevard to the bleak university housing estate where German friends of mine lived. They were Horst-Günther Krainick, a pediatrician who had founded the Hue medical school, his wife Elisabeth and his colleagues Raimund Discher and Alois Alteköster.

I learned that they had been on long lists bearing the names of educators, intellectuals, civil servants, priests and other notables drawn up in Hanoi. Eyewitnesses told me that North Vietnamese agents took these lists from house to house, arresting these people and hauling them before kangaroo courts for 10-minute “trials.”

Most were executed instantly; others carted out of town and killed later. The corpses of the German doctors were later found in a shallow grave close to the imperial tombs southwest of Hue.

I don’t know what happened to Ton That’s father, uncles and cousins. Their bodies were not in any of the mass graves found in and around the imperial city. I stood at one of those burial sites. South Vietnamese soldiers had discovered it when they spotted the beautifully manicured hands of women sticking out from the ground. It was obvious that they had been buried alive and tried to claw their way out.

With me was the late Washington Post correspondent Peter Braestrup. Pointing to the women, children and old men who had either been shot or clubbed to death, Braestrup asked a U.S. television cameraman, “Why don’t you film this scene?” The cameraman replied, “I am not here to spread anti-Communist propaganda.”

This episode seemed unfathomable but it was not unique; it simply reflected a pervasive mindset, which manifested itself most glaringly when actress Jane Fonda traveled to Hanoi and had herself photographed on an anti-aircraft gunner’s seat mockingly aiming her sights at what would have been American planes had they been around when this picture was shot.

As an old war reporter, I might be forgiven for melancholic reflections as I listened to the stories of Ton That, his in-laws and Hung. My point here is not whether the United States should ever have gotten involved in Vietnam but rather what madness caused the communist side to commit such unspeakable acts of inhumanity 40 years ago, and why did they ultimately pay off?

Many combat correspondents soon realized that the Tet Offensive was a major North Vietnamese blunder, a detail on which most military historians agree these days. At Tet ’68, Hanoi lost at least 45,000 men and its entire infrastructure in the South. And because of the massacres in Hue and elsewhere, it also lost much of its popular support.

Yet major United States media outlets portrayed Tet as a defeat for their own side. Before millions of viewers, two of America’s most respected television anchormen, Walter Cronkite of CBS and Frank McGee of NBC, declared the war “unwinnable,” prompting President Lyndon B. Johnson to say, “We have lost Cronkite; we have lost the war.” Following Tet, Johnson announced that he would not stand for re-election. Though a military victory for the United States and its allies, Tet ultimately marked the beginning of their defeat.

The world has moved on to different and potentially more terrifying conflicts. But this has not erased the memories of men like Ton That, Hung – or those sad ageing men Washington once conscripted to fight the first war America would ever lose: the Vietnam veterans.

In the mid-1980s, I was a chaplain intern at the VA Medical Center in St. Cloud, Minnesota. Along with psychologists, I formed two therapy groups of 60 former soldiers. Almost all of them had been called “baby killers” to their faces within 24 hours after their return from the Vietnam. Many had received “Dear John” letters from their wives or lovers while in combat; the girlfriend of one patient had cruelly sent him a video showing her in bed with a bearded peace activist.

Several told me how their pastors had ordered them from the pulpit not to return to church until their hair had grown back to civilian length. Many had attempted suicide. And all were broken men, destroyed by the behavior of significant segments of an ill-informed public who, like some journalists, politicians, intellectuals and pundits, had vilified their own countrymen in uniform while closing their eyes to their enemy’s heinous acts – crimes I saw with my own eyes.

– Uwe Siemon-Netto, a veteran foreign correspondent from Germany and a Lutheran lay theologian, is scholar-in-residence at Concordia Seminary, St. Louis.

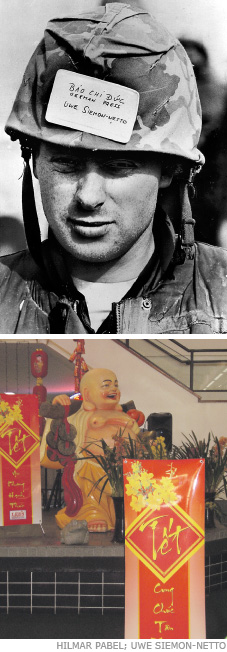

Pictures above: The author as a Springer News Service correspondent at Hue, 1968 (top). Reminders that Tet is a time to celebrate (below).